Oʻahu’s water supply is in crisis due to negligence from the colonial U.S. military. And it might not seem obvious to everyone that astronomers are implicated in the question of what happens next, but we very much are. Readers of my book The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred (details) will be familiar with the kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiian) struggle around Maunakea and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT). Without going into each little detail, the gist of it is that because Hawaiʻi was colonized by the United States, astronomers were given free rein to build telescopes on Mauna a Wākea, a volcano on the island of Hawaiʻi with excellent seeing. This is to say, it’s a great place to put a telescope, from the perspective of people who are focused on the best place to observe the night sky with a telescope.

In the decades since the first facility was built, 13 observatories have gone up on the Mauna, which in the view of kanaka cultural knowledge holders is not just sovereign kanaka land that has been colonized, but also a sacred place. Today, there is a proposal to build a 14th facility (and others will be decommissioned), the Thirty Meter Telescope, which is set to be the largest in the world. Construction on the facility was set to begin in 2014, but kiaʻi, Maunakea’s protectors, have successfully impeded its construction, often at great personal cost including criminalization by the colonial state.

In The Disordered Cosmos, I write about how the fight for the Mauna was life altering for me and has shifted my view on what science was and what science needs to be. Often framed as anti-science spiritualists, the kiaʻi are not just fighting to protect the Mauna from further desecration but also to transition from a colonial scientific practice to an ethical science, as Keolu Fox and I argued in The Nation. I think the piece that first really opened my mind about this was Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada’s “We Live in the Future. Come Join us.” where he writes:

That short-sighted model of “progress”—that we seem to be standing in the way of—hinges upon all of us, all of Hawaiʻi’s people, all of the Pacific’s people, all of the world’s people losing connection to land, to sea, to other human beings. The less you feel these connections, the easier it is for you to be convinced that unrestricted development is the highest and best use of land.

Part of what Bryan is writing about is the idea colonialist, racist idea that kānaka are backwards people who, by refusing the telescope and its potential economic gains, are refusing progress and inclusion in modernity. But who is really backwards here? It is in thinking with the kiaʻi and kanaka intellectuals that I came to fully understand that global warming is a technological development. Is that progress? Is modern life successful in a globally warmed world? Maybe technology isn’t actually synonymous with progress. A more modern viewpoint of the land is the one articulated by kanaka ways of seeing the world, understanding our interdependence on the land, our family.

Part of the task I took on in the discourse about the TMT was not just speaking as a Bajan in anti-colonial solidarity with my island kin, but also trying to educate myself and other members of the astronomy community about the context in which these telescopes have come to exist.

Importantly, this isn’t just about buildings on unceded land. This is also about the extensive damage that colonizers have done to the land. There is a long history here. This thread is captured in the Hawaii News Now (HNN) headline, “The bombing of Kahoʻolawe went on for decades. The clean-up will last generations.” The U.S. military chose one of the Hawaiian islands and bombed the shit out of it, for decades. Here is a photo, for which HNN wrote the caption, “When the military transferred Kahoʻolawe back to the state, the island was littered with tons debris and unexploded ordnance.”

kānaka maoli are aware that people come to their land and do what they want with it, without regard and care for this family member — or the people who have traditionally stewarded and been in good relations with it. They also know that across the Pacific Islands more broadly, this has been an ongoing problem. Nuclear weapons testing has irreversibly damaged the lifeways of so many living beings — and the land — in the Pacific.

Astronomers have to understand that no matter what we think our intentions are, ultimately observatories are disrupting the land, and this is part of a story that is bigger than astronomy and bigger than the beautiful images of the night sky that are so key to the work we do. And it’s easy to say, “Well our intentions are better” and “The bombing of Kahoʻolawe has stopped.” But here is a tweet from from November 29, 2021:

(JUST IN: The Department of Health warns against drinking & using tap water from the Navy water system. Residents at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam are complaining of a fuel or gasoline-like odor in the water. The Navy & DOH are investigating the source. Watch HNN for the latest.)

It is now 10 days later, and the crisis has only become more dire. The Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility — a fuel facility near Honolulu, Oʻahu that serves U.S. military operations in the Pacific — has leaked petroleum into the local water supply. This affects service members stationed there, yes, but more broadly, it affects kānaka maoli and other civilians. As the struggle at Standing Rock reminded us, water is life. This is not an inconvenience; it is a crisis for human life and the land — what we scientists are trained to call “the environment.”

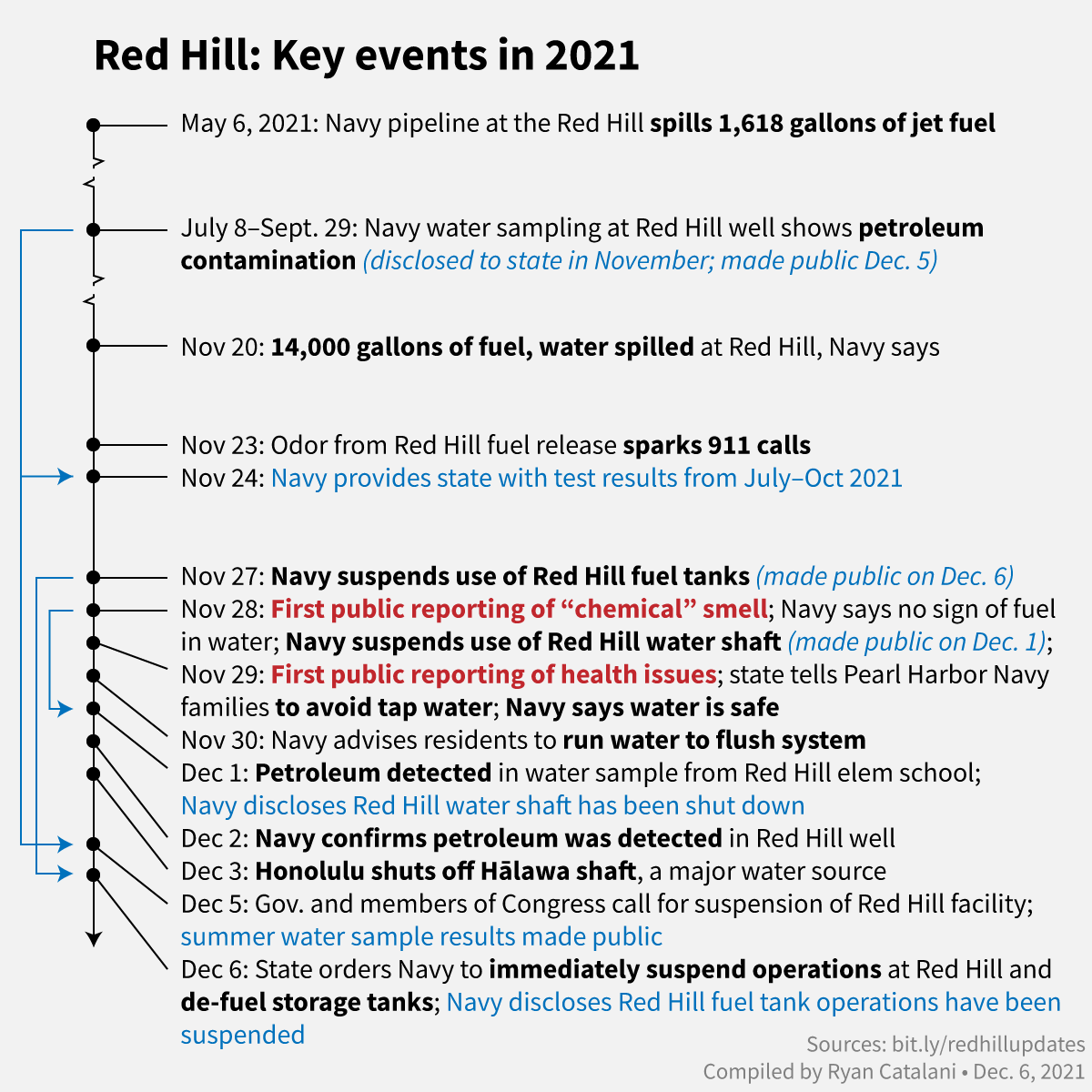

A few days ago, Ryan Catalani tweeted a figure with the question, “What did the Navy know, and when did they know it?” As you can see, the crisis began months ago:

The Biden Administration’s delay in protecting the public and the land is just the latest in a series of incidents over the course of more than a century where the colonizers have damaged the land and put its people at risk.

For me this brings to mind world renowned astronomer Sandy Faber’s call to arms for astronomers back in 2015: “The Thirty-Meter Telescope is in trouble, attacked by a horde of angry native Hawaiians...” (source). This comment was fully of dog whistles that evoke an image of kānaka maoli as violent savages who need to be put down, recalling the worst of colonialist white supremacy. It comes to mind now because of course they are angry. Even Jewish Jesus would be fucking angry about this shit. The land and the people — the whole community — has been poisoned and attacked over and over again in the name of “progress” and “safety.”

Imagine it was your community. In some ways I don’t have to imagine, really, because we have a PFAS-in-the-water problem here on the New Hampshire Seacoast, and my general response to it is, “What the actual fuck?” But I am a visitor on this land; it is not where my people are from. While I am responsible for being in good relations with it, it is not my native family (as it is for the Abenaki). I can only imagine the heightened anger and grief if it were.

When astronomers think about asking kānaka maoli for anything, this history must be part of the opening discussion. What is our responsibility to that history? As a professional group that has benefited repeatedly from the same colonialism that continues to damage the land and community relations, what does it mean for us to ask for more? Have we done our part to show that we can be in good relations with them?

What would it mean for astronomers, as a whole professional group, to be in good relations with kānaka maoli?

If the military continues to be a major source of distress for the community, what does astronomers’ ongoing positive relationship with the Air Force Maui Optical and Supercomputing observatory at Haleakalā Observatory on Maui tell kānaka maoli about our relationship with their priorities?

I can name specific people (nearly all of them white men) who would argue to me that Hawaiians need the economic investment that comes with the TMT. But why do they need the economic investment? Why is there so much money flying around in Hawaiʻi but so many kānaka maoli live in poverty in the midst of a housing crisis? Do they need the TMT or do they need capitalism to stop ravaging their communities?

It is up to us to ask this question and be willing to sit with the uncomfortable answer. kānaka maoli do not need astronomers or their so-called “gifts.” Astronomers need them, their land, and their continued economic oppression. This is a grotesque dynamic, and it is up to us to change it, including to understand that the answer to whether there should be more telescopes on the Mauna or Haleakalā might be “no” forever and ever.

Now is the time for astronomers to think deeply about how much we have benefited from Hawaiian resources. What will we do to restore the energy that we have taken?

Each day is a new opportunity for astronomers to stand in solidarity with kānaka maoli. In the case of astronomers, this requires not just being outraged by the damage to the environment, but recognizing that what is happening with #RedHill is part of a greater colonial history in which astronomy is also implicated. If you oppose the Navy’s damage to Oʻahu, think deeply about whether the plans for the Mauna are any different. Is it because you think your work — which depends on petroleum — is more noble than military work? Why are you so certain it is different or any better when so many experience them as differing tentacles of the same colonialism? ♥

To learn more about the history of astronomy in Hawaiʻi, I strongly recommend people check out Iokepa Salazar’s dissertation, “Multicultural settler colonialism and indigenous struggle in Hawaiʻi : the politics of astronomy on Mauna a Wākea.” You can find other relevant reading on the Decolonising Science Reading List.

If you want to help, some suggested resources are here.

Before you go: Consider grabbing a copy of The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred from anywhere that books are sold in hardcover, eBook, or audiobook format. Water Street Bookstore and Harvard Book Store may both still have signed copies in stock so maybe give them a call and support my local indies in the process.